ALEXANDRE PELLAES has worked with several multinational companies in Brazil. I interview him about his experiences with multicultural and remote teams. We discuss cultural differences and the importance of team agreements.

Subscribe to the Collaboration Superpowers Podcast on iTunes or Stitcher.

Please note: there were some technical issues up until 10.15. After that, the interview ran smoothly

Podcast production by Podcast Monster

Graphic design by Alfred Boland

More resources

Original transcript

Lisette: And we’re live. So welcome everybody to this Hangout on Air. My name is Lisette Sutherland, and I am interviewing people who are doing remote working well. And today I am speaking with Alex Pellaes. Sorry, I’ve already forgotten. I’m sorry for screwing up your name. Alex is a people management consultant in São Paulo, Brazil. Alex, you’ve worked with a number of multinational companies in Brazil and have been participating on multicultural and remote teams for a while now. So I wanted to talk to you about your experiences. So thanks so much. And for people who are listening in, you’re always welcome to send a tweet to #remoteinterview. If you have questions, use the Q&A.

Alex, tell me a little bit about yourself and your background. And how did you get started working on multinational and remote teams?

Alexandre: Thank you very much for the invitation for this interview. I’m talking from São Paulo. And my background is actually in finance. I graduated in accounting as my major. And I have a couple of MBAs and stuff too to complement [inaudible – 01:40] management skills. And I worked in several multinational companies in Brazil. [Distortion]. About eight years ago, I joined W.L. Gore, an American company that is very well known for a very unique culture. And I fell in love with the possibility of helping other companies to try different cultures [distortion – 02:34]. I don’t like the term [inaudible – 02:39]. I like to be seen as a challenging person inside a company just trying to take things out of the [inaudible – 02:48] way they do. And I’m very happy to do that with a couple of companies in Brazil right now.

Lisette: What is different about working in Brazil from the rest of the world?

Alexandre: There are many things. One of them is that Brazilians are very relaxed in their business connections. So it is very common for Brazilians to be late to their appointment. And Lisette can be testimonial of that because I was a couple of minutes late [inaudible – 03:24]. So it is expected when you [distortion – 03:30]. We are not proud of that, but it is expected. A 15-minute delay would be like tradition.

Lisette: Interesting.

Alexandre: Yeah. We [inaudible – 03:46] to foreigners when we’re going to deal with them and say, “You know, this is not disrespectful. It’s just the way it is.” And São Paulo has a very horrible traffic. And it just became the excuse to make sure we can be late, as we would be anyway.

Lisette: Interesting, okay.

Alexandre: And we tend not to be very straightforward. I think [distortion – 04:17]. We try to give soft feedback, and this is something that we are learning to improve because then we can send different sense of reality to people. And then we can really have a [façade – 04:32] on problems that will be bigger in the future. So we tend to be something that I don’t like about you or your work. I would be [inaudible – 04:45] and not be very straightforward. So you maybe did not understand that that was a negative feedback. So I require [inaudible – 04:56] for improvement. So [inaudible – 04:59] really see if the guys are giving [inaudible] good.

So I think in a nutshell, the [inaudible – 05:18] news doesn’t apply for Brazilians.

Lisette: Okay, very interesting. If you’re working on a multinational team, these things must really get in the way. If you’re working with a company who starts exactly on the hour, the meeting starts exactly on time. I’ve worked for this kind of companies. And five minutes late is five minutes late. Or a feedback, for instance, in the Dutch culture. Dutch people are very blunt. They just say it like it is. There’s no sugarcoating. They just state it. So this must be pretty shocking for people working in Brazil. Or is it an issue? How has that played out for you? On multinational teams, is that shocking for Brazilian culture? How has that worked?

Alexandre: It is. Brazilians tend to be very sensitive. So this is something that we try. We are becoming more and more international. So when you’re recruiting also, you start to include questions about feedback, how that person deals with feedback and how they are willing to change their way into the culture and be more flexible [inaudible – 08:04].

So this is something that we’ve been investing. Many companies in Brazil are investing a lot of efforts to really help people to feel more comfortable in providing and receiving feedback because we are bad at both.

Lisette: Right. How does that go then? Everybody needs improvement. Or maybe that’s just my skewed view. People do need improvement. People do need feedback. So when managers do that, are they giving it then in more of a soft way?

Alexandre: Yes, exactly. So what happened in the past is that all the feedback was really related to the delivery of their work and not about how they do. It was really about the what. And the golden rules of feedback in Brazil were you should not ask about the feedback. So you should just listen. You could not really try to understand better. You should just receive the feedback from your superior person, your boss, and just try to improve the delivery that the person would be asking you as an employee. So it was something really mechanical, really robotic.

And now what we are really going into is a different moment when we do not split person and employee. We see the whole thing. And then when you receive a feedback, it is a good thing for you as a whole. And we try to be very respectful but really straightforward. But this is really something we are learning. And in this very company, I tend to work with more flexible companies that are trying to have a different culture. And even when you approach those companies and say, “Hey, we have to work on the feedback skills of your team,” it comes all the prejudice from the past and they would say, “No, feedback is really hard because people are very reactive,” and blah, blah, blah and say, “Hey, this is the beginning of everything.” People have to know that they can speak out and they can hear in a nice way to improve their skills.

Lisette: Wow, very interesting, very interesting. What other challenges do you run into on multicultural teams? And maybe, well, let’s keep it to multicultural. I was going to say let’s make it specific to remote teams. But I guess maybe inherently, they all are remote if you’re multicultural. But what else comes up?

Alexandre: I think that Brazilians are very hard-working [inaudible – 12:57] mainly people from São Paulo but [inaudible] all Brazilians would go like that. They tend to work long hours. And they would tend to call you at any time. So if we are in a team working together, this would imply that I could call you [inaudible – 13:20]. So it would be a nice move to set the ground rules when working with people from Brazil because they would mix everything. They do not differentiate friendship from colleagues.

Lisette: Oh, that’s something important to note.

Alexandre: Yeah. So they would think that it is okay to ask very personal questions [laughs]. That is also shocking for foreign people from different cultures.

Lisette: Right. So really, don’t differentiate the friend-colleague line. It’s really life-work fusion. But people are people. So it seems like that can be a very good and bad part of working together if you’re not used to it.

Alexandre: Yes. So you could end up listening to problems from someone with their husbands or wives [laughs] [during a meeting – 14:13].

Lisette: Interesting. So when you do work on… Say you’re starting a new project with a multicultural team, multinational team. Do you actually sit down and define these ground rules before you start working with people?

Alexandre: No, that’s not common. That’s not a common thing. We are not good in planning, actually. We are good in executing. But we tend to skip the planning phase. So we go from idea to doing and we miss the planning part. And then during the execution, you just find out, “Oops, we never thought about this. We didn’t discuss [inaudible – 14:52].”

Lisette: The other side of that, there is an argument to be made that that is also a better way, which is you could also do all the planning in the world. And then once you start on the project, things come up you never thought of, and you spent all this time planning for things that never came up or just weren’t issues.

Alexandre: Yeah, you’re right. I agree with you. What I think we can do a little bit better is formalizing things. So we tend to be very informal. And then some of the agreements could be misunderstood. And then when you don’t formalize, you do not have a reference to get back and say, “Oops, I said A, you understood B, but we never cross-checked.”

Lisette: Right. And where would you formalize [crosstalk – 15:40].

Alexandre: This cross-checking.

Lisette: Oops, sorry.

Alexandre: [inaudible – 15:45] would be a very good strategy. And something that I’ve been applying a lot working with different cultures is really the reassurance of [their – 15:53] understanding. So if we’re saying something before we move on, we could just repeat that and say, “Okay, so what I understood from what you’re saying is this, this, this and that.” And then we say, “Okay, that’s you meant. Okay, let’s move on.” It takes a little longer.

Lisette: Is that documented anywhere? Or is it just a verbal agreement?

Alexandre: It’s commonly verbal.

Lisette: Okay, very interesting because I think these details really matter, especially when working remotely. If people are not aware of this, then it can cause probably all kinds of tensions on a team. So it’s just being aware of this.

Let’s talk about what works well on a multicultural or a remote team. What are the things that really go well?

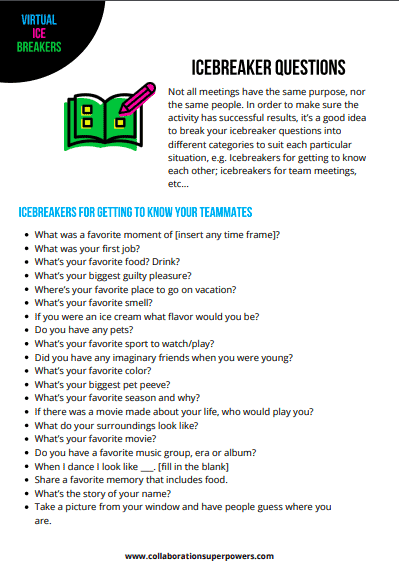

Alexandre: I think that first of all, people really should know each other and see the person behind the title or the job, whatever. We really have to relate to that person. That person has to matter, not only for the project but for you. I truly believe in this one-to-one connection as a person. So at the beginning of any kind of multicultural project, I think it would be a very recommendable exercise to know a little bit about each other. So one thing that I could tell you right now that could probably generate a better connection between us is I’m a father of triplets. So this is something that could generate some kind of sympathy, some kind of connection that if you could say, “Okay, if I am not in my best state,” you could probably say, “Hey, maybe he didn’t sleep so well. He’s just a human being.”

Lisette: Right. And [inaudible – 17:52] three children at once. That’s really something.

Alexandre: Yes, it is.

Lisette: Right.

Alexandre: And this is something really Brazilian. We would want to know a little bit about each other as a person. And this works very well. I’ve been working with teams from the U.S. and from Europe. And this kind of exercise works very well because then you just find out… When you’re working multicultural, there are things in the voice, there is accent, and there are problems with the language. Maybe someone can sound very arrogant because they do not have the vocabulary to show different ways of doing. Some other one may sound as they don’t care for similar reasons. So when you try to know them as a person, you just break all these assumptions that we do.

Lisette: Right. In fact, I did an interview with somebody last week who has created a game for virtual teams to help them get to know each other before they start working on a project. So you learn about their personality and their communication style. And his argument was that you wouldn’t just put a sports team together and say, “Go play a game.” You practice with them. You wouldn’t just put an orchestra in place and say, “Play the song.” You would tune first. He calls it kind of a tuning up for virtual teams when they work together.

Alexandre: Right, that is perfect. Yeah, that sounds exactly. I think what we have learned is that we will never really play multicultural teams in this very fast-changing world. We’ll never play as well as an orchestra, the whole thing and the rehearsals and everything. But we can play very well as a jazz band. So we can improvise. But you have to know what each one can provide to that group.

Lisette: Ah, that’s a perfect analogy. I love it. I love it. So it’s not an orchestra; it’s a jazz band. It’s a little more creative and experimental and maybe outside the lines of it.

Alexandre: Exactly.

Lisette: Oh, brilliant analogy. I want to talk about a story that you had emailed to me about an experience that you had while working at Gore. I thought it was a really great story. So I’d love if you told it again so that people can hear it.

Alexandre: Sure. When I joined Gore, I had just come from a controller position in another very traditional company. And it was really a process-oriented company. And when I joined Gore, I was learning about a whole different culture and more related to people and to the mission of the company and not really about the activities and the tasks. And I had this meeting with a lady in the U.S. And I think it was 11 a.m. We had scheduled this conference from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. I think it was Brazilian time. So we did the first half of this one-hour conference at first. And then the lady said, “Hey, Alex, do you mind if we get back at 2 p.m.? We just stop, have a hard break now. And then we get back at 2 p.m.” I just take a look at my agenda and say, “Okay, that’s not a problem. I can do it.” And she told me, “You know, I have to walk my dog.” And I just say, “Okay, sorry, I think I didn’t understand what you’re saying.” And she left and she said, “No, Alex, you probably understood. I am really going out to walk my dog. I live near the plant here at Gore, and my dog has been wit me for 12 years, and he’s ill. So a couple of times during the day, I just go walking there and walk with my dog for a couple of minutes and then get back to the office.” And the interesting thing of this story is my reaction. I really felt angry at first. I said, “Okay, this showed no commitment. This person is really not committed with the success of this company.” And this was the controller in me talking. And then I stopped a little bit to think and say, “How nice of her to tell me the truth because she could have told me anything.” I was in a different country, a different time zone and everything, but she had chosen to tell me the truth. So I really tried to see that as a proof of confidence and trying to bond in a stronger connection. And then my anger became happiness. I said, “Okay, that’s good. So this probably means that she’s trusting me enough to tell me this.” And when she came back, I thanked her for being honest to me. And the meeting went very well at 2 p.m. And probably, if we had continued at 12, she would be worried with her dog. So it was very nice. And this showed me a new side of the remote and the multicultural work. That is the transparency. You really have to be transparent.

Lisette: In terms of becoming more personal, personalizing the remote experience.

Alexandre: Exactly.

Lisette: Okay. Also, the other thing that you bring up is the word trust, which is a huge issue on remote teams, the idea of how do you build trust. And what’s been your experience with that? I know there are some cultures that are not trustful from the very beginning. I spoke with a woman from Columbia who said that trust just isn’t in the culture. So remote working simply doesn’t work in Columbia as well. But is it the same in Brazil?

Alexandre: No, I wouldn’t say that. I think that it’s probably the other way around. We will tend to trust. So we would believe that if someone says that they are going to do something, they will do. And the problem specifically is that as we tend to be very soft in the feedback, if we don’t deliver what we promised, it would take a while for us to really go and say, “Hey, you owe me that.” And this is something that we have to find a sweet spot to work on.

Lisette: I see. What are the ways that you’ve seen that people build trust on the remote teams that you’ve worked on?

Alexandre: I think that delivering what they committed is the best way. One of the sayings that I like the most, for remote teams, it works very well. I think it goes like that: “Taking a commitment generates hope, and fulfilling a commitment generates trust.”

Lisette: Oh, wow, I love it.

Alexandre: So this works very well for this remote work. So when you say that you’re going to do something, I’m hoping you will. But when you fulfill that, then I trust you. And then for the next interactions, it’s there.

Lisette: Indeed. And I agree with you. I think reliability is probably the number one thing that builds trust on a team. It’s just knowing that you can count on when somebody says they’ll do something, then they actually do it.

Alexandre: Yeah. And I think that for remote teams, there is no risk of over-communication [inaudible – 25:42] really keep the flow going, keep the information coming, and do not assume that somebody will understand if you’re not communicating something. They will not. We really need all the information possible.

Lisette: And that brings up the next question, which is what are the tools that you use to communicate? What has worked best for you? Is it an instant messaging system or Skype?

Alexandre: I work a lot with Skype and emails. I think they are the best. When you’re creating things at the same time in different parts of the world, then instant messaging is very helpful too.

Lisette: Okay. And are there any other tools that you use like Google Docs or Trello?

Alexandre: I try to use Trello, but I think not everybody in the team had committed to use the tools. So it was not good. We do use Google Docs a lot to make sure that we can work on the same document and make sure that we have it updated so everybody can see what is going on, even if they are not involved in that specific moment.

Lisette: Right. Yeah, it’s very handy to be able to see what else somebody is writing in real time, if that’s possible, or to come back to it later and edit it later. I do love it for that. Okay, interesting.

Now I want to move into a subject of work-life balance, which is something that lots of people talk about, the fusion of work and life. And I think that remote working really offers a little bit more of that fusion. You could work from home. You could work while traveling. You could work at your own time. So I wanted to ask you about what work-life fusion looks like in Brazil. Is that a new thing? Or is that just something that’s…? Because you were saying that the professional and the non-professional life sort of blends. But does it also blend in terms of the work and the non-work life?

Alexandre: It does. We’ve been talking a lot about the work-life balance. And there are several meanings actually in Brazil. I think that when you have people more experienced, more senior, it tends to be actually a negative impact because once you have more remote tools, you tend to work from home even when you should not be working. So it is very common to have people with notebooks at 11 p.m. in the bed and just working there. It’s just they can’t help. It’s there. It’s easy. Let’s advance something for tomorrow. And I think that people are still not prepared to take advantage of the remote tools during the day. So for me, it is very natural. For instance, my triplets have birthday last Monday, so it was super okay for me to go with them to the bowling. And I could work with my cell phone, and I would be in touch with everybody. So I could experience my work-life balance. But I think this is exceptional. It’s really not the rule. [inaudible – 29:08] We still have a lot of companies with a very bossy structure. So they would tend to not understand when an employee needs to do remote work. But they would expect the employee to use the tools in other hours than the working hours.

Lisette: Ah, interesting. So within the Brazil culture, it’s okay to call it any time. [crosstalk – 29:35] working remotely, the danger is then you are never turning off because…

Alexandre: Exactly.

Lisette: Yeah. So people who are working remotely tend to work more than people that if you’re just in the office because at the office, you’re there. Well, actually, no. It would be totally different. It would be people are still working all the time because it’s so fused.

Alexandre: Yeah, exactly.

Lisette: Wow, super interesting.

Alexandre: We have tried. I have seen a couple of companies in Brazil trying to work with the home office style and everything. But I think that people are misunderstanding that. So companies are still not feeling comfortable yet with that alternative. So you have people saying, “Okay, I’m going to work at home office today.” We use exactly this expression in English. We could say we are doing home office. This is how Brazilian will say. And you could call that person and they would say, “Okay, I have a doctor appointment. For now, I can talk.” I say, “Okay, sorry, I thought we were doing the home office.” This is not home office. You’re taking the day off to go to the doctor. So it’s still not clear to the workforce as well. So I think it’s in the middle of the transition.

Lisette: Okay. But now is remote working something that is transitioning then in Brazil?

Alexandre: Yeah.

Lisette: Okay, so more and more people are doing it. And why? What is the main reason that more and more people are doing it, or the main reasons?

Alexandre: I think that one of the reasons is that some people [inaudible – 31:27] that they are more productive working at home offices a couple of days a week because the company environment can be full of distractions. So this is one. Of course, we have the other group that could not work at home at all. Also, it’s becoming more expensive to have people at the office. So some of the job proposals are already considering home-office facilities and agreements.

Lisette: Interesting. So the office space is simply just becoming too expensive for a small or medium-sized company to even consider.

Alexandre: Yes, exactly. São Paulo is a very expensive city. So if you’re going to set a team that can work remotely, that would be an advantage for the company.

Lisette: Okay. But most companies aren’t doing this because they don’t really have a way of knowing what people are working on when they’re working remotely. And also, people are using the term ‘working remotely’ when they really do need to just take the day off to go to the doctor.

Alexandre: Yes, exactly. So big traditional companies are flirting with this idea, but they are still not secure about it.

Lisette: And what would help them be more secure, I wonder? Is it just a matter of time? Is it a matter of setting guidelines? Any insight into that?

Alexandre: I would think that time, for sure. But also, if they can clarify the meaning of the home office and really specify what it means… Because also, I think that the employees themselves feel guilty when they do home office because while still learning how to do that, they may not feel comfortable. I’m working in my pajamas, so maybe I don’t feel I’m working. And [inaudible – 33:36] Brazilians oversensitive.

Lisette: Right. And it is very luxurious to work from home anyways. You can be in your slippers. You can get the cup of coffee any time you want or take a walk.

Alexandre: Exactly. So we’re still finding a way to be productive doing that. And I think that companies can help really setting the guidelines and showing people that they can be productive. It’s really educating them for a while.

Lisette: Right, and what it means to set up a home office and what do you need and how [inaudible – 34:07] work. Now I can imagine that there are certain personalities. Probably, you’ve come across it with the people that you’ve worked with, people that are just not good at working from home. So you’ve come across this. So what happens in those circumstances? Do they just give up and come back to the office? Who have you found is it that can’t work at home?

Alexandre: I think that young people still have a hard time [inaudible – 34:32] working at home. I would not recommend the first years of employment with heavy load of home office. It is a learning process. And I think that one-to-one connection, the personal connection is much stronger in that. And it can be very lonely when you’re working at home office. And it could be not so creative. There are a lot of people that really need that energy from other people around. Even if they are not working together, they are there. And they overhear something there and just throw an idea or receive an idea. So I think this environment, at the beginning of their careers, is very interesting. I don’t believe there is a career itself anymore as it was in the past. But I consider that career right now is just a series of meaningful experience that has been [inaudible – 35:33] with a meaningful narrative. But for a young person, they need to be with more people. I think that’s very healthy for them. I think it’s challenging in a good way.

Lisette: That real-time collaboration, bouncing ideas off each other, and really being saturated in a culture.

Alexandre: Yes, exactly. That’s what I mean.

Lisette: Ah, interesting. I have not heard that before. So when you’re starting your career, just go into the office. Get to know people. See what the culture is like. And then after you’ve developed your strength and the line of work that you know and love, then maybe it’s good to take a step back and to be productive in a place or to learn how to work with people before you go remote.

Alexandre: Yes, yes.

Lisette: Super interesting. We’re almost at the top of the hour. We’re at the end of the time. One more question is if people want to know more about you and what you do and the projects that you work on, where can they find you? What’s the best way?

Alexandre: They can find me at LinkedIn. They can see my profile there. It’s still in Portuguese, but we will manage that in English as well. And I will release my website in the end of this month. It’s called xboss.com.pr. And there I’m going to talk a little bit about non-traditional organizational structures.

Lisette: Interesting. So the hierarchy versus the network versus all the other structures that we have out there.

Alexandre: Yes, exactly.

Lisette: Ah, that will be very interesting, especially to the Happy Melly audience out there.

Alexandre: Good, good.

Lisette: Ah, great. Thanks so much today for the time. And sorry for the technical issues that we ran into. But I think in the end, it all worked out. I think there is some very good information here. Are there any other tips or advice that you have for people who want to work on a remote team?

Alexandre: I think just the challenge. And I think the [inaudible – 37:50] really don’t forget that it is a person working in the other side. Even if you’re not seeing and you don’t know exactly how they are feeling, just practice empathy. This is really crucial for that.

Lisette: I love that, practice empathy.

Alexandre: Yeah.

Lisette: Yeah, be human. Remember that we’re all human in that people have bad days. With triplets, in some nights, you probably don’t sleep [laughs].

Alexandre: Yeah, [inaudible – 38:16].

Lisette: Exactly. All right, thanks, Alex, for all of your time and your insight. I really appreciate it. I look forward to writing this up on the blog for collaborationsuperpowers.com. And until the next time, everybody, be powerful.